The origins of the row of cockle sheds situated along the creek in the old town of Leigh-On-Sea, Essex can be traced back to a time when they were little more than wooden shacks sitting in front of an ever-growing mountain of discarded shells. No. 1 Cockle Shed Row was run by Richard HARVEY from c.1892, who was from a local Leigh fishing family and was amongst the first to start selling directly from the sheds.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Leigh’s trade consisted mainly of shrimp, oysters, mussels, whelk and winkle. By the 1850s the oyster and whelk trade was all but abandoned, and by the early 20th century the fishing industry had been almost entirely replaced by cockles.

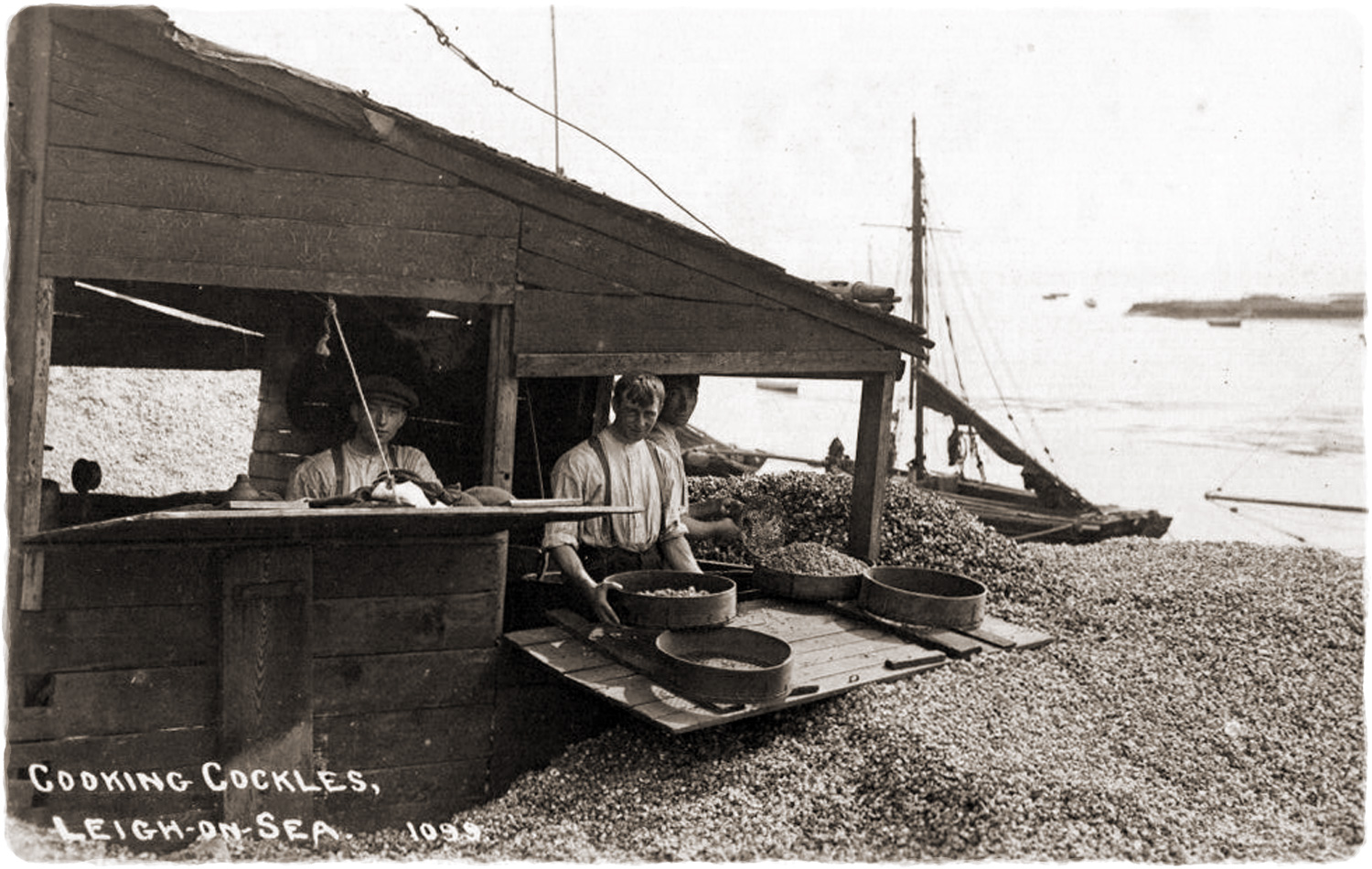

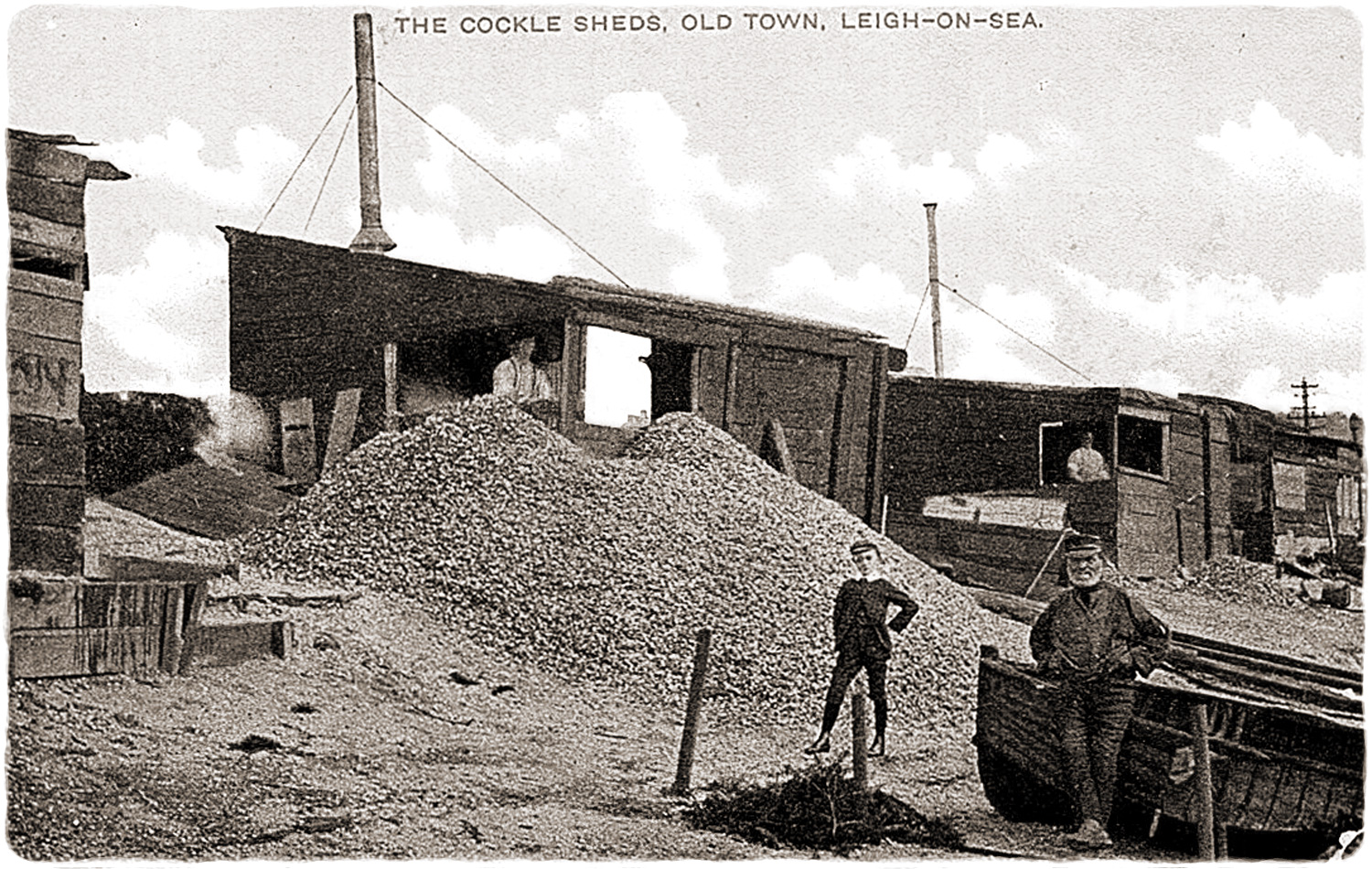

- Cockle Sheds (c.1912)

Richard HARVEY was born in early 1864 in Leigh and was the eleventh of twelve children born to William HARVEY and Emma GOSS. William was born in 1819 in Leigh and worked as a fisherman, as did his father Daniel HARVEY. Richard’s paternal great-grandfather was John GOING, a local corn and coal merchant of some wealth. Emma was born in 1824 in Prittlewell, Essex and the daughter of agricultural labourer Henry GOSS who was originally from Suffolk.

When the 1841 census was taken William was age 21 and living with his parents, Daniel and Sarah, in a cottage on Billet Lane, Leigh, whilst Emma was age 15 and living with her parents, Henry and Ann, on North Street, Prittlewell. They married on 16th Jan 1843 at St Clement’s Church up the hill in Leigh when they were 23 and 19, although Emma stated to be 20. Emma was also five months pregnant at the time, with their first child born in May, followed by another eleven over the next twenty-four years. William’s father died the following year aged 62 and was buried in St Clement’s churchyard on 5th Apr 1844.

- William Harvey (1843-1893) – fisherman, m.1869 to Emily Harriet Warrick Quilter

- John Harvey (1844-1904) – fisherman, m.1866 to Mary Ann Newman

- Daniel Henry Harvey (1846-1827) – fisherman, m.1870 to Mary Ann Elignor Robinson

- Emma Harvey (1849-1915) – charwoman, m.1868 to William John Little (fisherman)

- Henry Harvey (1851-1852) – died aged 14 months

- Eliza Ann Harvey ( 1853-1915) – m.1875 to Arthur Robinson (fisherman, lockman then barge foreman)

- George Joseph Harvey (1855-1917) – fish hawker, m.1875 to Emma Elizabeth Kerry and c.1895 to Louisa Hannah Margaret Emmerton

- Samuel Harvey (1858-1938) – fisherman, m.1880 to Louisa Jane Ellis

- Ann Harvey (1860-1927) – domestic servant, nurse then charwoman, unmarried

- Joseph Harvey (1862-1879) – died aged 17

- Richard Harvey (1864-1929) – fisherman & cockle merchant, m.1888 to Harriet Louisa Phipps

- Henry Goss Harvey (1867-1939) – fish porter, m.1888 to Eliza Alice Ellis (sister of Samuel’s wife)

When the 1851 census was taken, the Harvey family were living on “Leigh Street” and their youngest child was just 6 days old and yet to be named Henry. Emma’s mother, a nurse, was also present on the night the census was taken. Tragically, Henry died at fourteen months old at the beginning of Jun 1852 and was buried in St Clement’s churchyard on the 4th.

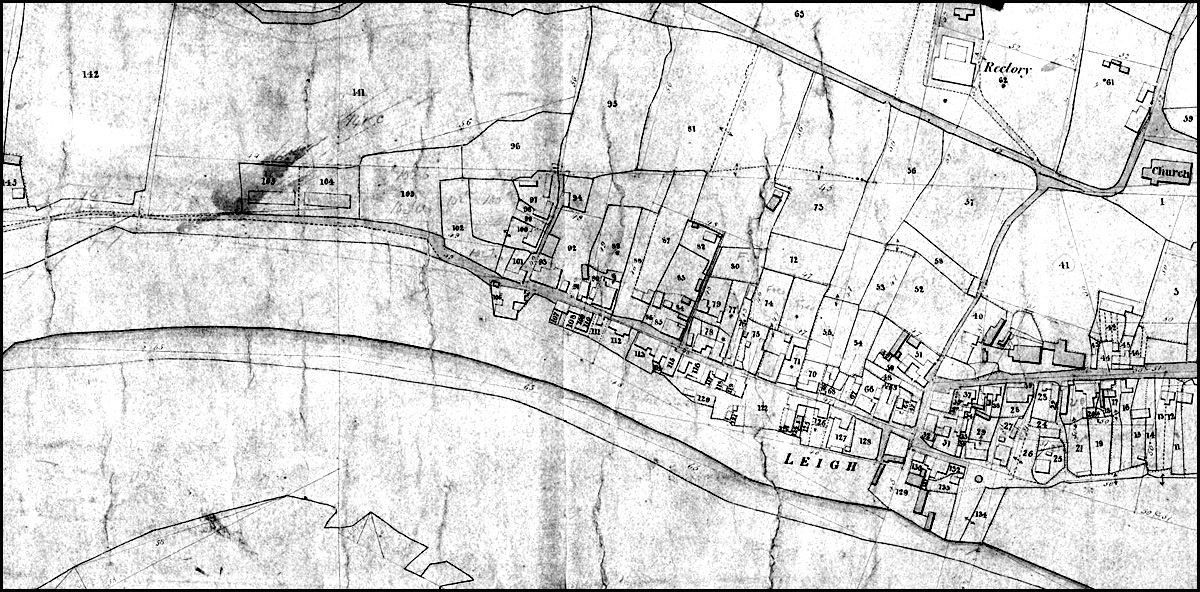

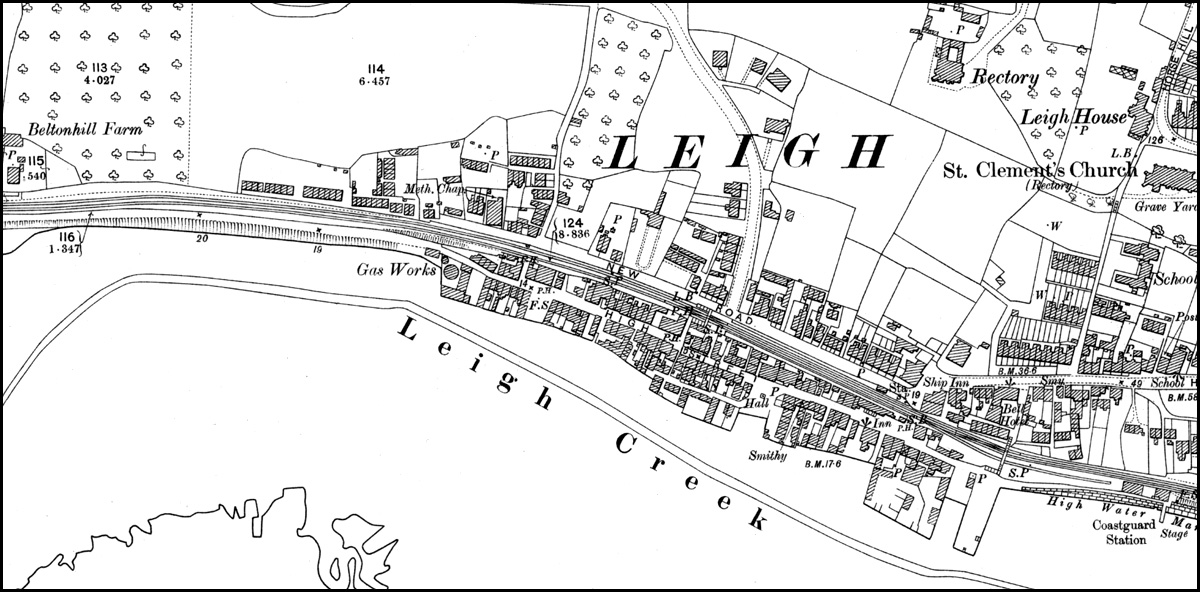

The 1847 tithe map of Leigh (below left) shows the old town just before the railway line carved its way through the houses during 1854, with the station opening on 1st Jul 1855. At this time there were several hundred acres of oyster pits off the shore in Leigh Creek, whereas in Southend the beds were used for muscles. After the railway arrived the village was much changed, with many of the old unsanitary hovel-like cottages swept away. The line opened up opportunities for the local fishermen, enabling a more reliable carriage by rail of their oysters, winkles, muscles and shrimps into London for sale.

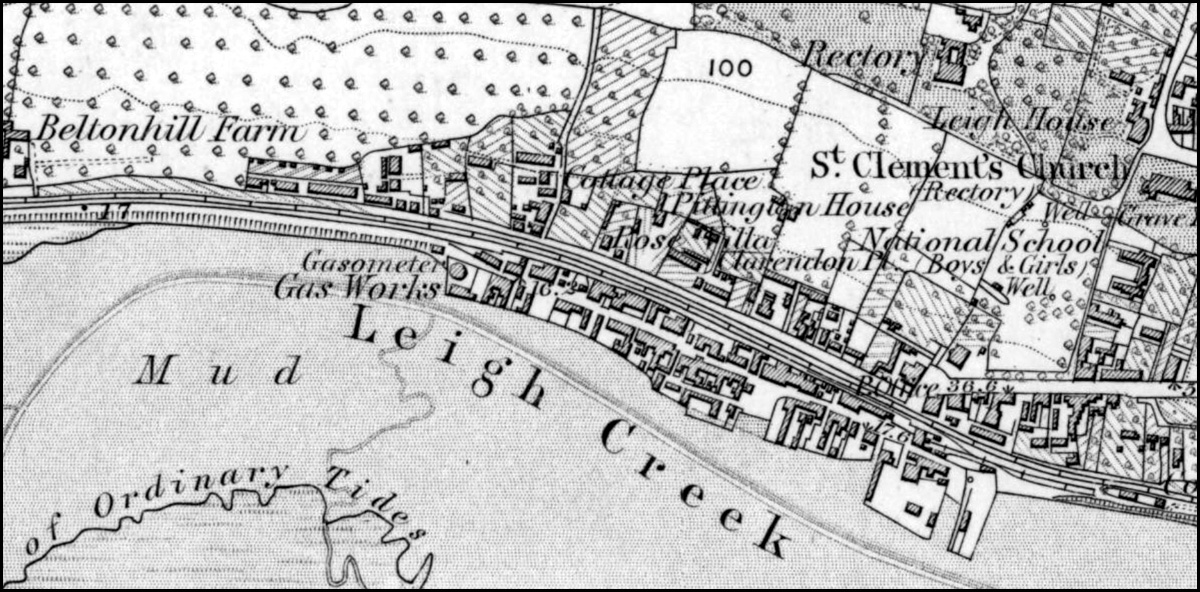

William’s mother died in 1858 and was buried in St Clement’s churchyard on the 22nd Mar. The Harvey family were living on Alley Dock when the 1861 census was taken, just off the High Street. The lane still exists but there are no cottages to be found on it now. In 1866 part of the wharf fronting the creek was sold by owner William FOSTER to the new Leigh Gas Light And Coke Company in order to light the town up, and a gasometer and associated buildings were erected just along from the cockle sheds. Emma’s father died the following year in 1867 aged 77 and one month later Emma gave birth to her twelfth and final child, naming him Henry after her father and the baby they lost in 1852. The family were still living on Alley Dock when the 1871 census was taken. Richard was now age 7, and his three eldest brothers and eldest sister were all married with children of their own.

- Leigh Tithe Map 1847

- Essex Sheet LXXVIII Surveyed 1873, Published 1880

On 20th Oct 1879, Richard’s brother Joseph died aged 17 (Richard was 15). The family were living on the High Street when the 1881 census was taken and Richard was now working as a fisherman, most likely with his father. Younger brother Henry (age 14) was also working as a fisherman and they were the only two children now left at home with all but one other sibling now married. Richard’s father William died later that year aged 62. Up until the age of 22, Richard had been fishing for shrimp, then in 1886, just before marrying Harriet, he took up cockling. In 1881 Harriet, age 18, was working as a general servant in Leyton, Essex. Perhaps her work took her further into southeast Essex, where she then met Richard.

Richard HARVEY married Harriet Louisa PHIPPS in early 1888. Harriet was born in 1863 in Broxbourne, Hertfordshire and was the second of five children born to Alfred PHIPPS, a general labourer for the New River Company, and Susannah HARKNETT, the daughter of a shepherd. The PHIPPS family moved to nearby Cheshunt where Harriet’s mother died when she was fifteen in 1878. Her father swiftly remarried to Mary Ann Prior DAY on 11th Jan 1879. Mary was fourteen years his junior and an unmarried mother of two young children at the time. Harriet’s father went on to have six more children with his second wife between 1879-1893, all born in Cheshunt. Mary died in 1909 aged 61 and Alfred died on 19th Dec 1919 aged 83 (both in Cheshunt).

Richard and Harriet had eight children born between 1888-1904 but sadly lost their fourth child at under 3 months old, and their last two children at ages two and one.

- Alfred Vincent Harvey (1888-1963) – Fisherman

- Gilbert Harknett Harvey (1890-1954) – Fisherman then Shellfish & Poultry Merchant

- Bertha Rosetta Harvey (1892-1979)

- Mabel Harvey (1895-1985) – died under 3 months old

- Herbert Owen Phipps Harvey (1897-1978) – Cockle Salesman & Fisherman

- Alice Glenrosa Harvey (1899-1957)

- Clifford Goss Harvey (1901-1904) – died at age 2

- Irene Harriet Coleman Harvey (1904-1905) – died at age 1

In 1891 young family was living at the recently erected 1 Mulberry Cottage on Billet Lane. Richard (age 27) was working as a fisherman, with the census noting he was an employer. His mother Emma was living on her own, occupying two rooms on the High Street, aged 66 and working as a laundress and fishnet knitter. To aid with his fishing, Richard procured boys from the Rochford Workhouse to teach his trade.

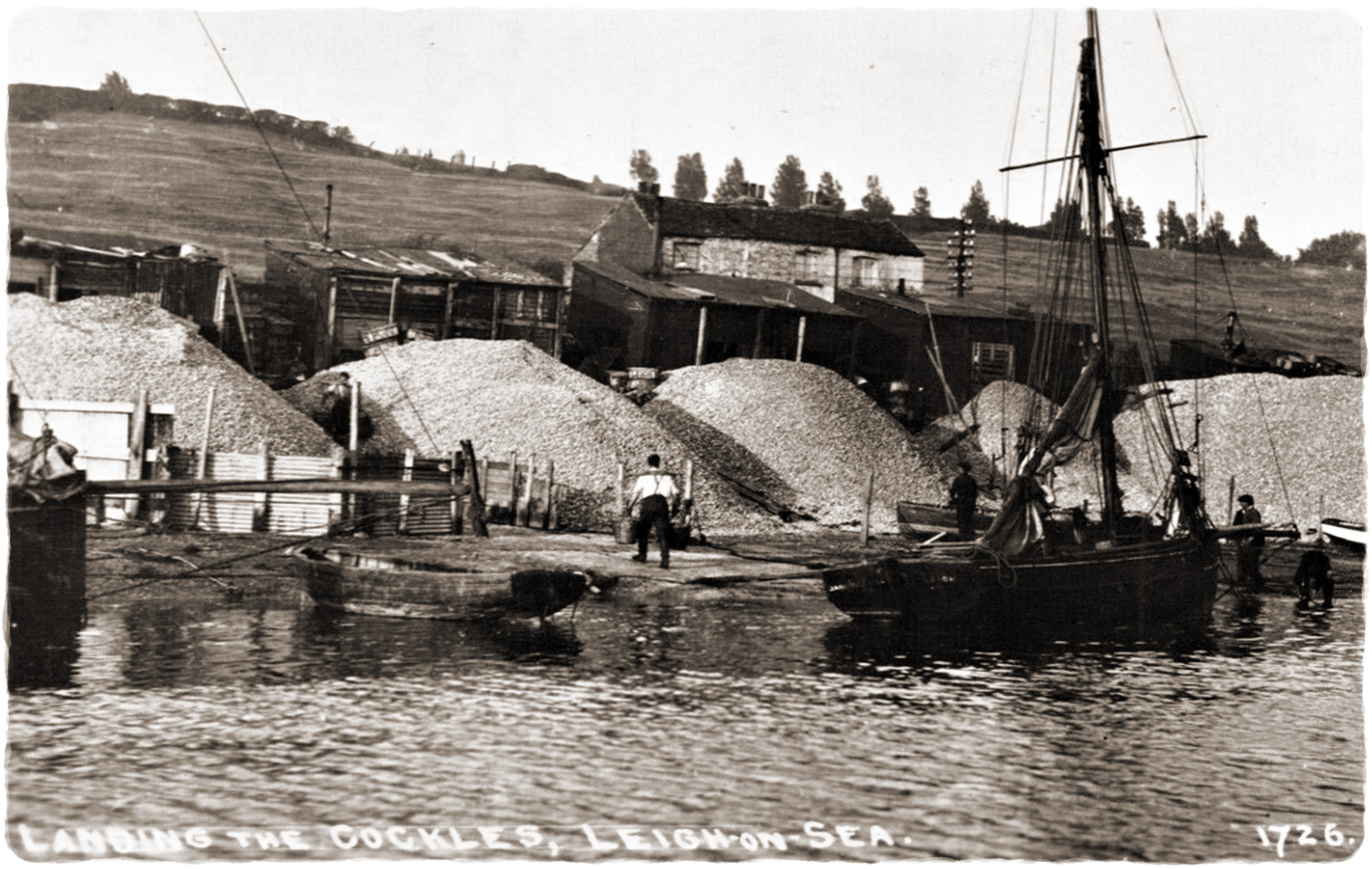

Offensive Smells

The year 1892 was full of many events, both for Richard personally and for the cockle fishers generally. Firstly, it was during that year that Richard, according to one of his descendants, first started working from the cockle sheds. There were about 100 cocklers working from Leigh at that time, who would go out on their smack and rake cockles from the seabed between low tides, filling wicker baskets which would be emptied into their boats. On returning to Leigh basket loads would be carried to the creek tied to yokes and the cockles would be washed in the water for a few days to clear them of sand. The next part of the preparation process involved briefly plunging the cockles into boiling water en-mass before being separated from their shells in a large sieve. The cockles were then washed three times before being ready for sale. The shells were discarded out the back of the sheds, which gave off “a most offensive smell” as any remaining flesh decayed. Notice to abate the nuisance was served to all the owners of the cockle boiling shanties in August of that year, with one John HILLS simply returning the letter as “refused“, clearly not wanting to change how he did things nor find the stench offensive. To make matters worse, mingling in with the reak of rotting cockles was the delightful scent of manure as it was carted through Leigh from the wharf into Hadleigh to the Salvation Army’s newly established Farm Colony. The occupiers of the cottages just opposite on the other side of the railway line must have had a lot to put up with!

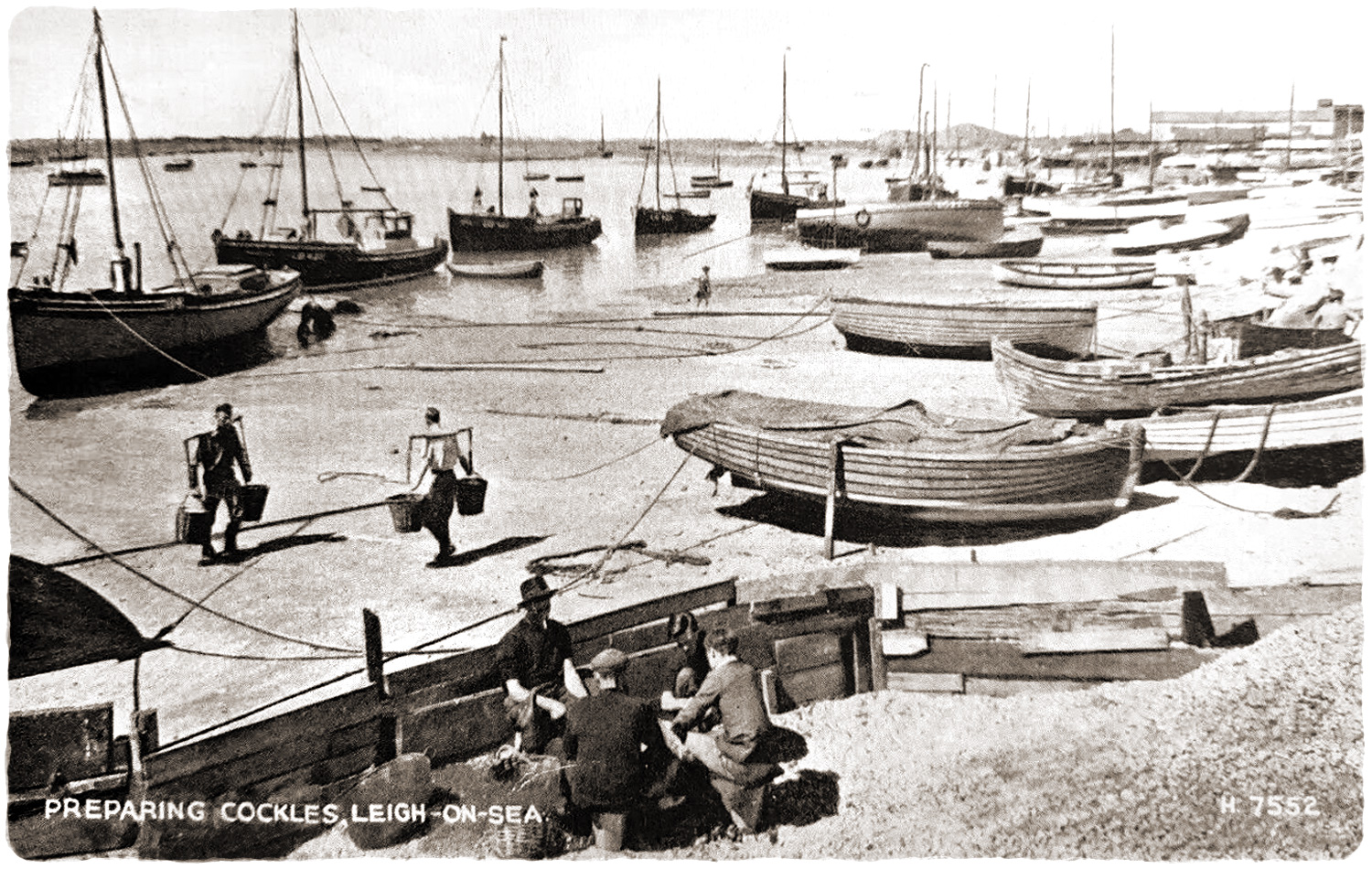

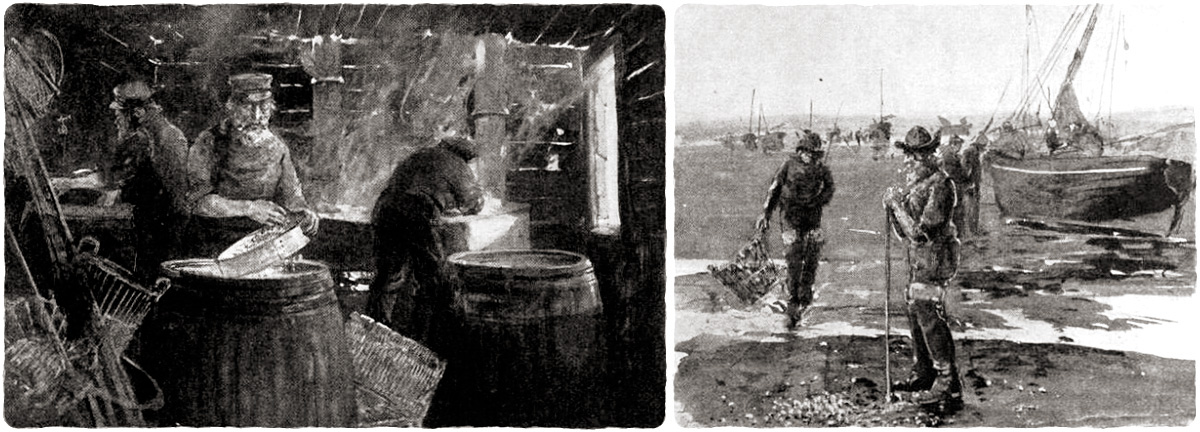

These old photographic postcards capture the landing, carrying and cooking of cockles at Leigh in the early 20th century.

- “Landing The Cockles, Leigh-On-Sea”

- “Preparing Cockles, Leigh-On-Sea”

- “Cooking Cockles, Leigh-On-Sea”

- “The Cockle Sheds, Old Town, Leigh-On-Sea” (1922)

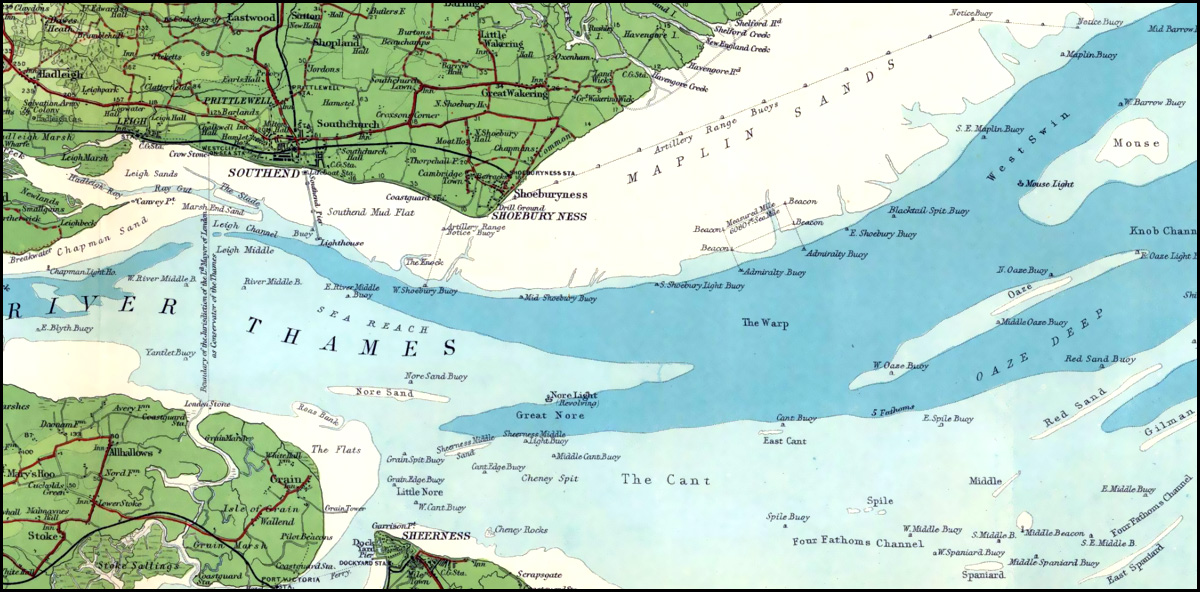

Target Practice Off Sheereness

Just prior to the matter of unseemly odours, a much more serious event occurred that threatened to jeopardise the livelihoods of the cocklers. In May 1892, a number of Leigh fishermen attended before the Departmental Committee which was inquiring into the issue of off-sea target practice near Sheerness, Kent, situated on the opposite side of the River Thames from Shoeberyness. The army wanted to impose a bye-law to regulate their sessions in two areas east and west of Sheerness and create a protected area from fishing vessels. Unfortunately for the fishermen, these were the same two areas used for cockling and catching shrimp, being choice fishing grounds used by several hundred men every day. The nearby Maplin Sands off Shoeburyness, Essex had previously been closed for artillery practice, so they were understandably upset at the prospect of losing another fishing area along with one or more days of work every month. The fishermen were mostly happy to continue as things stood, simply avoiding gunshot from the warships. One of the fishermen who attended was Richard’s brother William, who was also a member of the Fisheries Committee for Kent & Essex. He stated how he had “collided with one of the targets” and how the firing from Sheerness was “not always so particular as they ought to be.” Another brother, John, who was also a fishery officer, stated that they were “inconvenienced by the firing from the forts, but they would rather keep on in the same way“. He also stated how the warships came and placed their targets, and had “had shot very close to him.” This seems to have been an ongoing issue and was still causing problems in 1929.

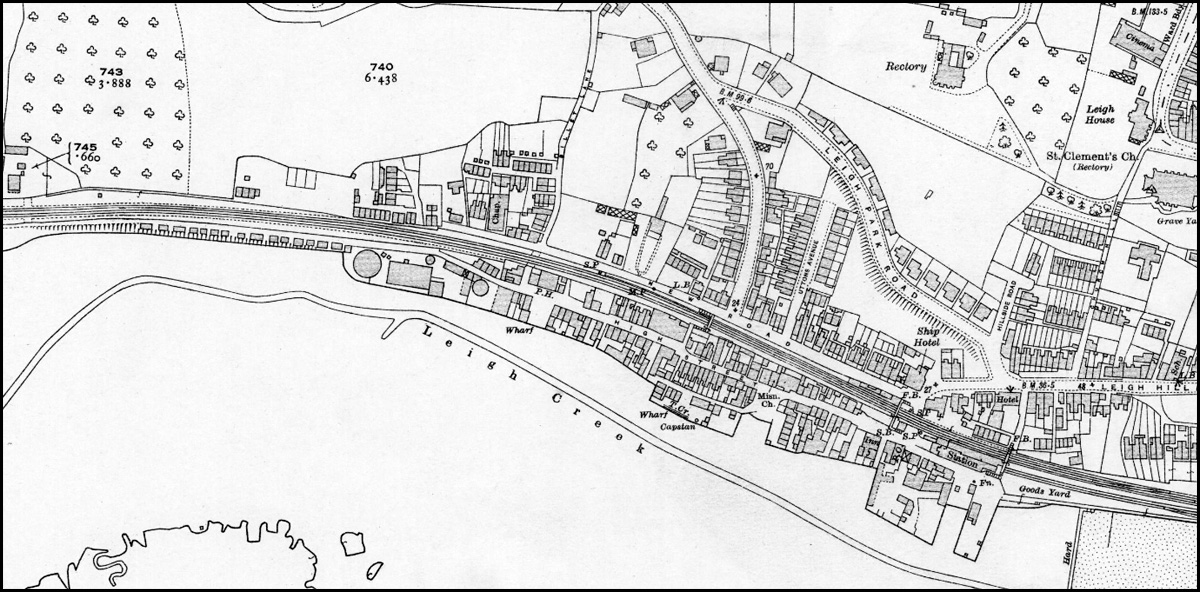

- Sheet 26 Essex, Published 1903

Drowned Off The Nore

The last big event for Richard during that year happened on 27th Sep 1892, when his eldest brother William, aged 49, drowned after his boat capsized whilst rescuing the crew of a small yacht. William had been working with his brother Samuel just prior to his rescue attempt on their fishing smack “Gertrude” and had been instrumental in the rescue of the crews of many small yachts over the years. A reward of £2 was offered for the recovery of William’s body, which was found two days later on a sand bank three miles from Whitstable, Kent by his brother John and bought back to Leigh. The inquest noted as a sideline that William could not swim. During the well-attended funeral the following week, Richard was “seized with a fit, which lasted several minutes.”

Richard and Harriet lost their fourth-born child as a baby during the beginning of 1895, and in early 1898 Richard’s mother Emma died aged 74. By 1901 Richard had built three cottages called Fairlight, Clifton and Brookfield on Billet Lane, apparently erected overnight to avail Southend Council who were trying to stop the work! The family moved into “Fairlight Cottage” where Richard continued to work as a fisherman but was noted as a “worker” this time, whilst his brothers George and Daniel were both fish merchants with their “own account“.

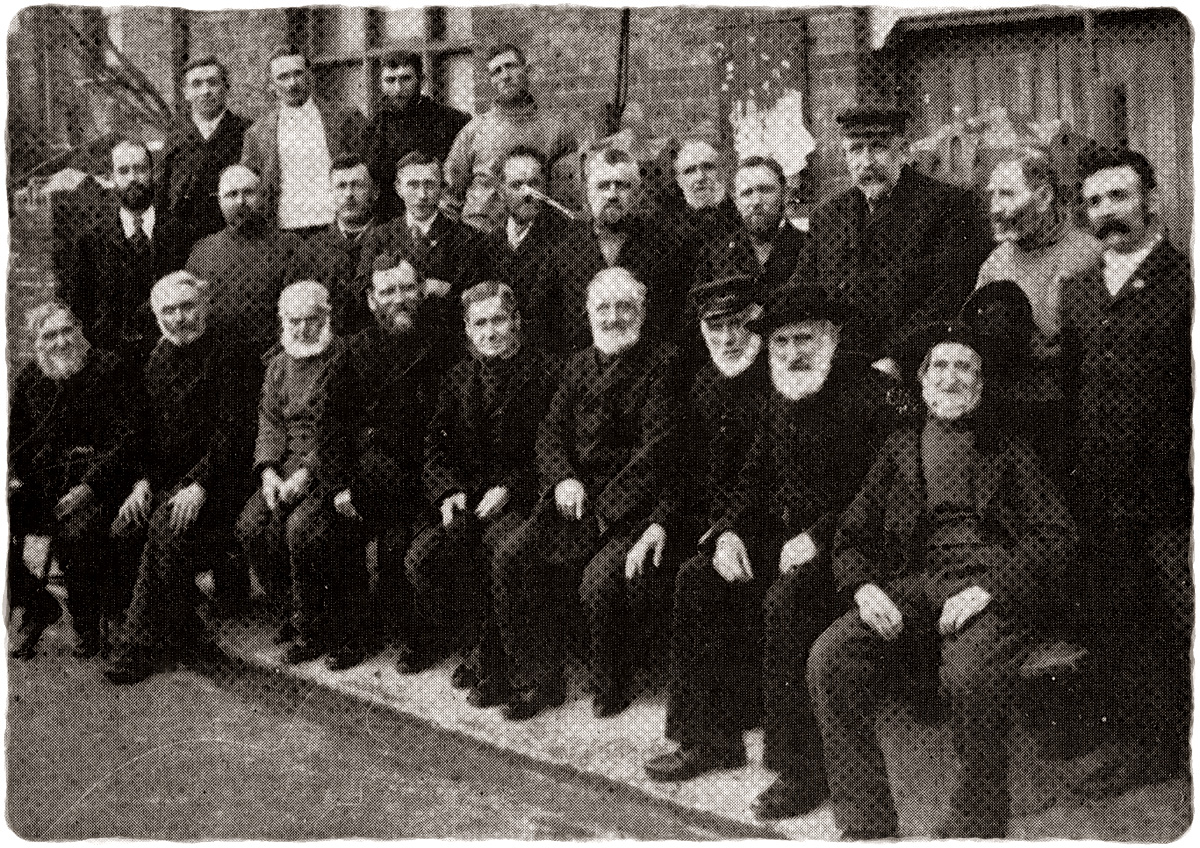

This wonderful photograph was taken in 1902 and captures the Leigh fishermen who were members of the “society class” of Old Town Methodist Church. Richard HARVEY (age 38) is centre row, third from the left.

- Leigh Fishermen 1902

Leigh’s Suspected Cockles

The same year the above photograph was taken were several cases of Typhoid fever both locally and in London, and the source was traced back to Leigh’s cockles. Leigh Creek was situated just over a quarter of a mile from a sewage outlet, and the cockles had become polluted as they lay there (ironically) for cleaning. The boiling process was also found to not be of sufficient length to kill the bacteria, and a change from boiling to steaming thoroughly took place (although some small-scale sellers continued to use copper pots). Many fishermen did not believe the outbreak had been adequately traced back to Leigh and so continued to lay their cockles in the creek, with several more cases of Typhoid fever being reported and Leigh cockles being temporarily banned from sale at Billingsgate Market in London. The Illustrated London News ran a large article entitled “Microbes In Molluscs” in Feb 1903 with drawings by Charles de Lacy.

By 1905 Richard had saved enough money to pay off the loan used to build Fairlight, Clifton and Brookfield, but had to spend it on the installation of new cockle steaming apparatus.

Cockles were still causing outbreaks of Typhoid in 1908 and again traced back to Leigh. It was well recognised now that Leigh Creek was contaminated with sewage and that the cockles needed to be cooked thoroughly before being sold, so the local Rector and one resident were appointed to ensure that the instructions of the Fishmongers Company were carried out by all cockle sellers lest they lose their livelihoods.

“Leigh cockle-boilers at work. The man nearest the window is boiling the cockles, the foreground and other figures are detaching the shells and washing the mollusc in a sieve through three waters. The boiling process is useless as a disinfectant.”

- “Leigh Cockle-Boilers At Work” and “The Source Of The Shell-Fish Contaminated In Leigh Creek”

“The source of the shell-fish contaminated in Leigh Creek. The cockles dug on the Maplins are laid in Leigh Creek to clear them of sand, and become polluted by sewage. They have been condemned by the Fishmongers’ Company.”

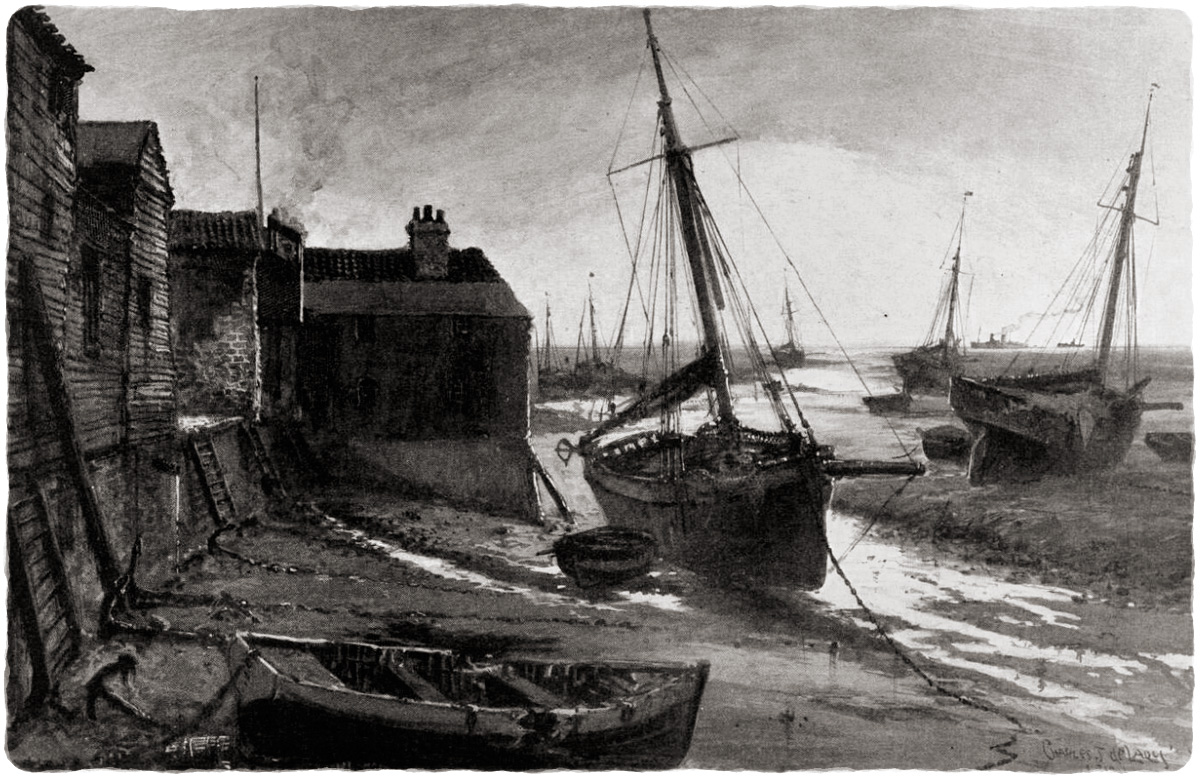

- “A Cockle-Boiling Hulk At Leigh”

“The impurity of Leigh cockles : The sewage-polluted creek, Leigh-On-Sea, where the shell-fish were contaminated. The creek, our Artist notes, was covered with mud, refuse, and slime. The Medical Officer for the City of London visited the creek on January 3, pronounced it “obviously filthy,” and condemned it as a place wherein to deposit cockles. Leigh cockles are taken from Maplin Sands, and laid for a few days in the creek to clear themselves of sand. Half a mile above this spot the Leigh sewage is discharged. The boat is a typical Leigh “borley” of fifteen tons.”

- “The Impurity Of Leigh Cockles : The Sewage-Polluted Creek, Leigh-On-Sea, Where The Shell-Fish Were Contaminated”

In mid-1904, Richard and Harriet’s two-year-old son Clifford died, just after the birth of their eighth and final child, Irene. A few months later on 19th Dec Richard’s brother John died suddenly at the age of 60, and in Jun 1905 their daughter Irene died aged 1.

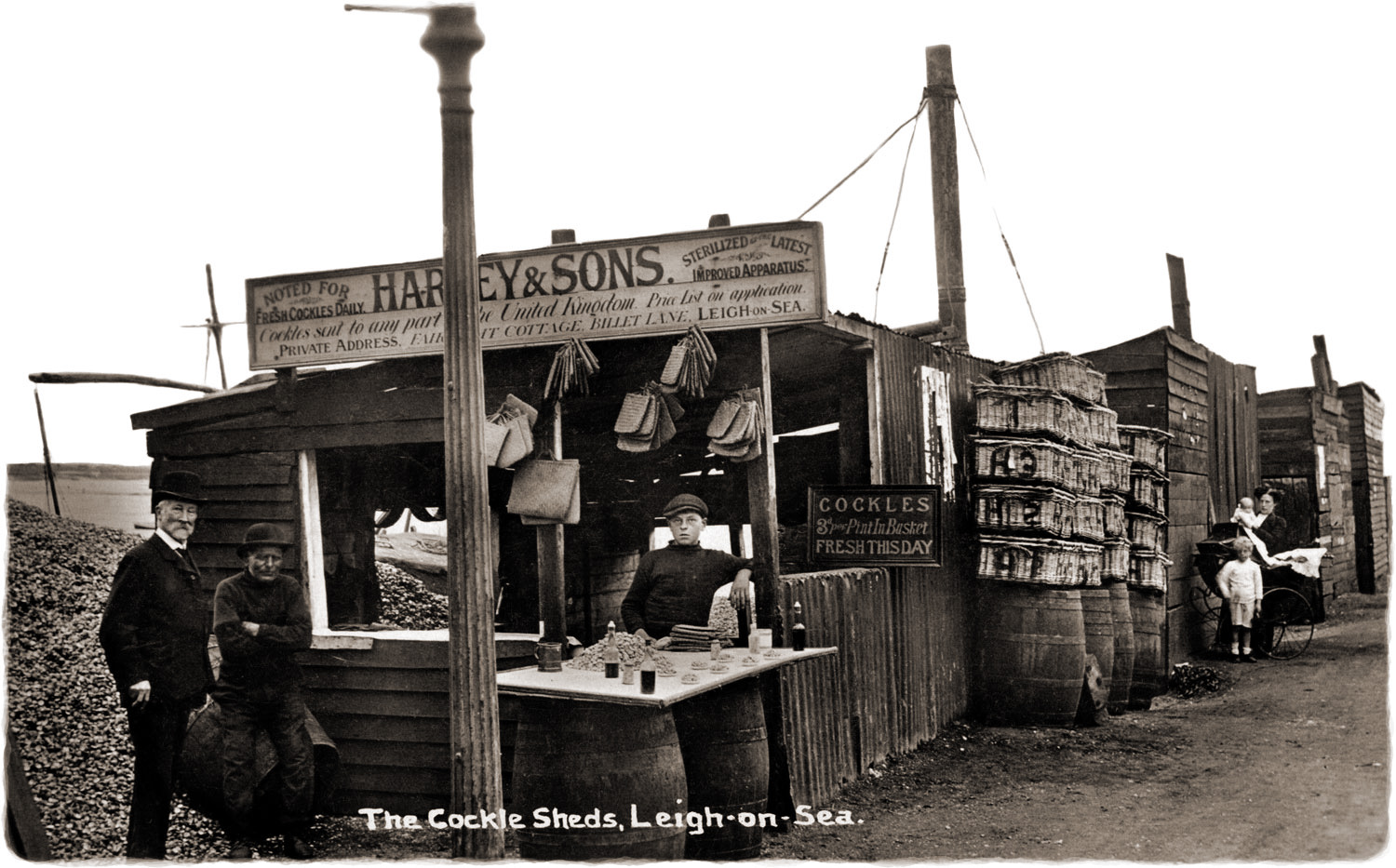

In 1907 and 1908 Richard advertised a cottage to let, described as “6 rooms, good drying ground, every convenience“, possibly one of his two cottages next door to Fairlight. In 1911 Richard was working as a fisherman (employer), and sons Alfred (22) and Gilbert (20) were also working as fishermen, most likely for their father. “Harvey & Sons, Cockle Merchants” was first listed in Kelly’s Directory in 1910 at Billet Lane, then from 1912 to 1922 at Fairlight Cottage.

The gentleman in the 1912 photograph below in the bowler hat with folded arms is Richard HARVEY and the boy is his youngest son Herbert. The older gentleman was a local schoolmaster, but the lady with the two young children is unknown. Note the signage boasting their daily fresh cockles to be “Sterilized By The Latest Improved Apparatus“, which cost 3d per pint. Of the four sheds in the photograph, this is the only one with a prominent sign, or even open for business.

- Harvey & Sons, 1 Cockle Shed (1912)

Gilbert joined the dock police at Tilbury in 1911 due to cockling becoming bad but went back into the business not long after. When war broke out, sons Alfred and Herbert joined the Royal Navy both serving between 1917-1919. Alfred served aboard the Vivid, Queen, Duke and then Vivid again. Herbert served on the Vivid, Thalia, Victory, Reswich, Victory, Queen and Venerable. Richard’s sisters Emma and Eliza both died in 1915 (age 66 and 62), and his brother George died at Rochford Workhouse on New Year’s Eve 1917 aged 62.

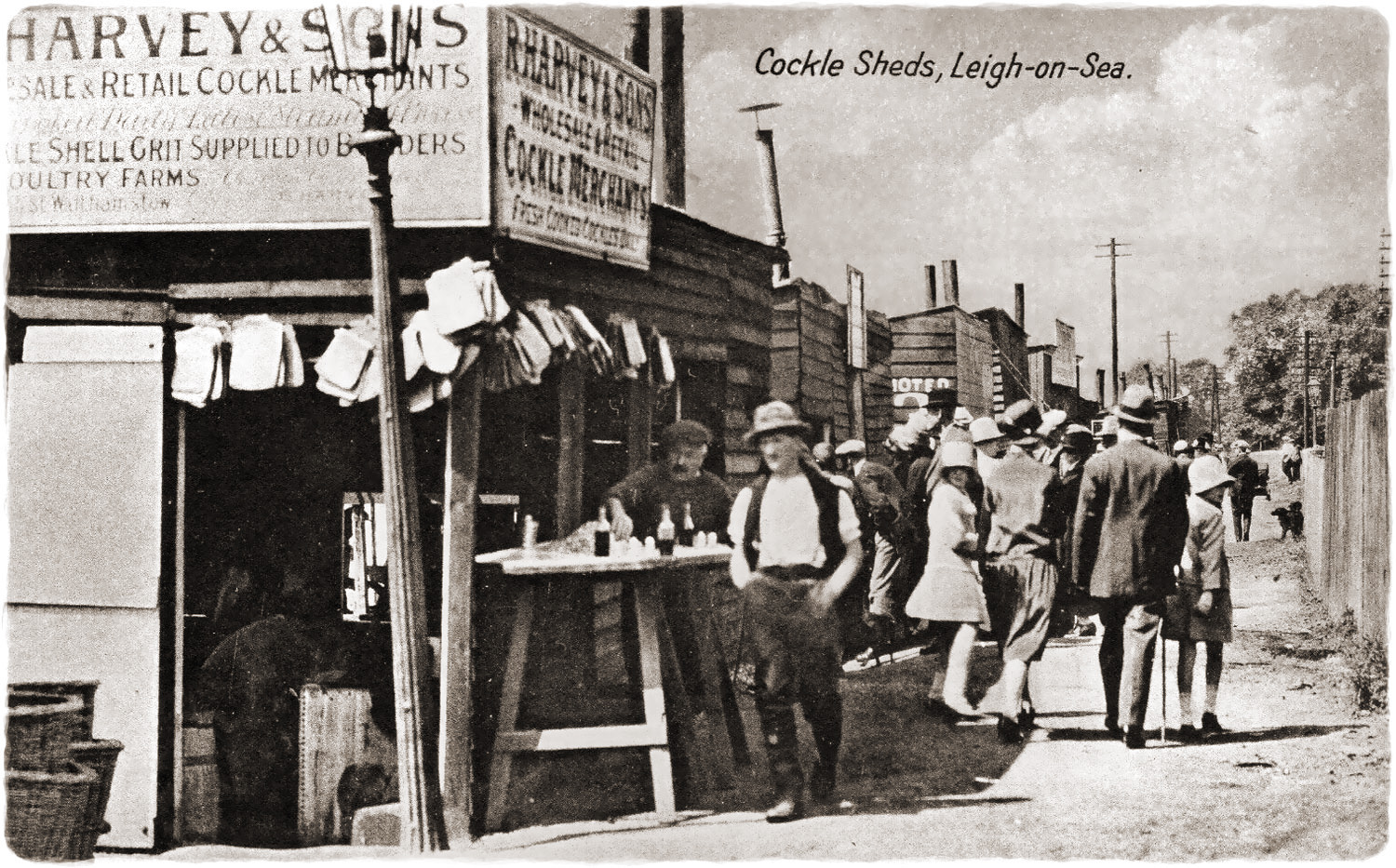

Richard and Harriet had moved to “Broxbourne” on Westleigh Avenue, Leigh by 1921. The cottage was named after Harriet’s birthplace. Richard was age 57 with the occupation “Shellfish Merchant, Employer“. He worked from “The Marshes, No.1 High Street, Leigh“, and employed local fishermen brothers Ernest and Archer COTGROVE. Their daughter Bertha was performing “home duties“, and their daughter Alice was working as an invoice typist. Their son Herbert was working with his father from the same address, also noted to be an employer. Their son Gilbert was now living at “St Kilda”, Glendale Gardens, Leigh with his wife Annie and three of their eventual four children. He was working as a shellfish merchant, and an employer of no fixed place (ie. at sea), and employed Francis NEWLAND and brothers Albert and Alfred NOAKES as fishermen. Their son Alfred had married just before the war began and was living on Billet Lane with his wife Edith and the first of their two children. He was working as a fisherman (employer, of no fixed place).

The signage in this 1920s photograph stated that Harvey & Sons were now wholesale and retail, and supplied cockle shell grit to builders and poultry farms. The shed had now been extended up to the lamppost.

- Harvey & Sons, 1 Cockle Shed (1920s)

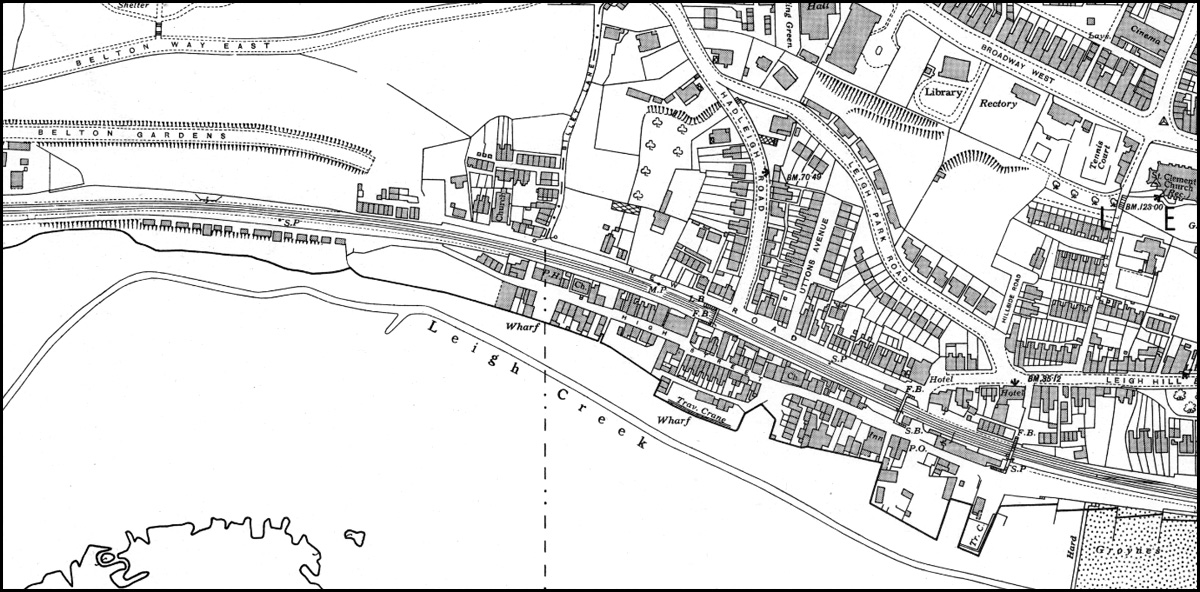

The cockle sheds were not included on maps until 1922, most likely because they were wooden shacks of a temporary nature in the 19th century. There were fifteen distinct blocks, one of which was later shown to be a double block making sixteen in total. There is still the same number of sheds today.

- Essex (1st Ed-Rev 1862-96) LXXVIII.9 Revised 1895, Published 1897

- Essex (New Series 1913-) n XC-4 Revised 1920 to 1921, Published 1922

Richard’s brother Daniel and sister Ann both died in 1927, aged 81 and 66, followed by his wife Harriet on 20th Feb 1929 aged 66. Richard died just over one month later at Westcliff Nursing Home on 23rd Mar aged 65 after falling out of bed whilst recovering from a prostate operation. The last of Richard’s siblings died in 1938 (Samuel aged 80) and 1939 (Henry aged 72).

The cockling business was left to his three sons, who continued to run it under “R Harvey & Sons”. It was listed as “Leigh Marshes” in Kelly’s Directory from 1929. Gilbert owned 50% of the business, whilst Alfred and Herbert owned 25% each. The 1939 Register, taken in October, recorded Alfred working as a fisherman, Gilbert as a shellfish and poultry merchant, and Herbert as a cockle salesman and fisherman. During WWII Gilbert was the Port Fishery officer, taking orders from the War Office. In 1940 six Leigh boats with volunteer crews were commandeered by the Royal Navy to aid with the evacuation of Dunkirk, the Harvey’s “Defender” being one of them. Gilbert was awarded an MBE in 1948.

- Cockle Sheds (1952) Britain from Above #EAW041993

Leigh train station was re-sited in 1934 to its current position just west of the cockle sheds, and the gasometers and associated buildings had been removed by 1939/47 (as can be seen on the left map below). The area remained empty for some time until the railway line flyover and car park were approved to be built in their place in 1955/56, although the work didn’t begin until the end of the year and took quite some time to complete.

- Essex (New Series 1913-) n XC.4 Revised 1939, Published 1947

- Google Maps 2023

The Harvey cockle business continued to run from 1 Cockle Shed for many years, with Herbert’s home as the contact address for the business up until he died in 1978. Both brothers had predeceased Herbert, Gilbert dying in 1954 aged 64 and Alfred in 1963 aged 74). The business became incorporated on 29th May 1979 (now dissolved), and one of the directors was also a director of Coral Island Seafoods, part of Kershaws Frozen Foods in Scarisbrick, Merseyside. No. 1 Cockle Sheds was listed as the trading address for Coral Island Seafood which then changed its name to Kershaws Quality Foods. The business stopped operating as a shellfish plant in 2003 and in 2007 Kershaws Seafood added an extension for seating. In 2008 it changed into the Simply Seafood restaurant and takeaway with Kershaws Seafood still associated with 1 Cockle Shed up to 2018. “Simply Seafood” closed down in 2020, and in 2022 a new restaurant simply called No1 Cockleshed opened up and extended into the takeaway section (sister business to Ocean Beach in Southend). Thus the link back to the Harvey family ends.

Along with the restaurant at no.1, there are currently two fishmonger shops in the row (West’s Seafoods and Osborne & Son), with nearly all the others used as the processing plants for West’s Seafoods, Osborne’s, Thameside Shellfish and Deal Bros. The ground of the working area at the back is still covered in crushed shells, flattened to form a hard surface.

- 1 Cockle Shed, Belton Bridge & Car Park

- Cockle Shed Row

- High Street, west of the Cockle Sheds

- Leigh Creek, west of the Cockle Sheds

- Behind The Cockle Sheds

- Behind The Cockle Sheds

- Behind The Cockle Sheds

- Crushed Shell Floor

Videos of the cockle industry of Leigh-On-Sea from the 1940s to the 1980s.

Resources & References

I use many different resources during my research, a majority of which I do online. Many thanks to Richard’s grandson (also named Richard) for a few extra details about his family.

Internet:

- Ancestry – www.ancestry.com

- Britain from Above – www.britainfromabove.org.uk

- British Newspaper Archive – www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk (also available on Find My Past)

- Echo – www.echo-news.co.uk

- Essex Archives – www.essexarchivesonline.co.uk

- Essex Society for Archaeology & History – www.esah1852.org.uk

- Facebook – www.facebook.com

- Find My Past – www.findmypast.co.uk

- Google – www.google.co.uk

- National Library of Scotland (maps) – maps.nls.uk

Newspaper articles reproduced with the permission of the British Newspaper Archive and The British Library Board.

Maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Books:

- Leigh-On-Sea A History by Judith William (2002)

- Old Leigh by H. N. Bride (1954)

- The History of Rochford Hundred by Philip Benton (1867)

If you have any questions regarding my research or would like anything added or amended, please contact me. I’m also available to hire to trace family trees.

- “Cockle Boats Unloaded” (The Sphere, 15 Oct 1955)